What is the Early History of Airships?

Michael Anissimov

Michael Anissimov

The history of airships begins on 8 August 1709, when Portuguese Jesuit priest Bartolomeu de Gusmao successfully floated a ball to the ceiling of the Casa da India in Lisbon, by means of combustion. Surprisingly, this is the first verified historical reference to any type of powered (non-gliding) airship. Earlier references to powered flight or airships are purely mythological, such as the Greek legend of Icarus. Bartolomeu de Gusmao's demonstration was in the presence of the royal Court of Portugal and King John V, who had originally provided the funds for the endeavor. He had plans to produce manned airships, but he died before they could be carried out.

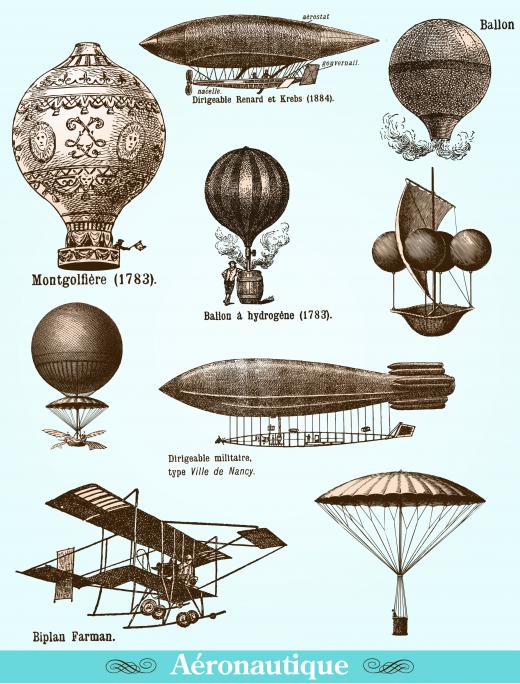

Little else of importance in the history of airships occurred until almost a century later, in June 1783, when the Montgolfier brothers, French inventors who began as paper manufacturers, built the first legitimate flying machine in human history. It was a globe-shaped balloon with a volume of more than 28,000 cubic feet (about 793 cubic meters) and an internal fire to generate hot air for lifting. They performed this feat in front of a crowd of dignitaries, and news of it reached most of the French elite. The flight was unmanned, covered 1.2 miles (2 km), lasted ten minutes, and reached an estimated altitude of 5,200 to 6,600 ft (1,600 to 2,000 m). A few months later, in September, they built a similar balloon and flew it with the first living beings to engage in powered flight: a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. This demonstration was in front of the French Royal Court, and impressed a huge crowd.

Only a few weeks later, in October, the Montgolfier brothers were ready to launch a historic milestone: the first humans in powered flight. They prepared by engaging in experiments with tethered manned flight, using the 26-year-old physician Pilatre de Rozier. The first experimental flight was on 15 October, followed by another flight in front of scientists two days later, and a third experiment on 19 October with Andre Geroud de Villette, a wallpaper manufacturer from Madrid. The flight with Rozier and de Villette reached 324 ft (99 m) within 15 seconds, along restraining ropes.

The historic moment — the first manned airship flight in history — occurred on 21 November, at the grounds of the Chateau da la Muette in the western outskirts of Paris. Pilatre de Rozier was joined by marquis d'Arlandes, an army officer, and flew in an elegantly decorated blue balloon for about 5.6 mi (9 km) across Paris, at an altitude of 3,000 ft (910 m). After a 25 minute flight, the balloon landed between a pair of windmills in the Butte-aux-Cailles area, outside the ramparts of Paris at that time. Numerous additional balloons were built after this first success, and a balloon craze swept the country of France.

The later "Age of Airships" didn't begin until the year 1900, and it ended in 1937 with the Hindenburg disaster.

AS FEATURED ON:

AS FEATURED ON:

Discussion Comments

@bythewell - People do still use hot air balloons as a kind of personal transport, although it's usually for the novelty rather than for any other purpose. But with roads and cars at the stage of technology we have them in the modern world, I'm not sure it would be possible to design a lighter than air transport that would be worth it in any kind of commercial sense.

@Fa5t3r - I don't think it was a very efficient way to travel, even aside from the safety issues. It must have been pretty slow compared with flying in a plane. It looks amazing and maybe it would have been better for personal air transport because it isn't as complicated and powerful as a plane, but flying giant explosive bags all over the world wouldn't have been a very popular idea.

It seems like almost every alternate history film or show depicts the world as being a different dimension by including airships as a viable means of transport. I have always wondered if that is actually what might have happened. I suppose the idea is that if the Hindenburg didn't go down, airships might have continued to gain in popularity and the age of airships would never have ended.

But is that actually what would have happened, or was the Hindenburg disaster going to happen eventually one way or another? The fact that they were using such flammable gas to move people around isn't exactly safe. And if it was possible to become safe quickly, then surely they would have done so rather than abandon the idea altogether.

Post your comments