What is the Motor Cortex?

The motor cortex of the brain is a region in the posterior part of the frontal lobe that controls voluntary movement. Neurons in this region of the brain send signals down the spinal cord to the muscles to coordinate movements. The motor cortex is divided into regions that represent the regions of the body, and neurons in each region correspond with the movements in the related part of the body. This area is also involved with learning movements and coordination.

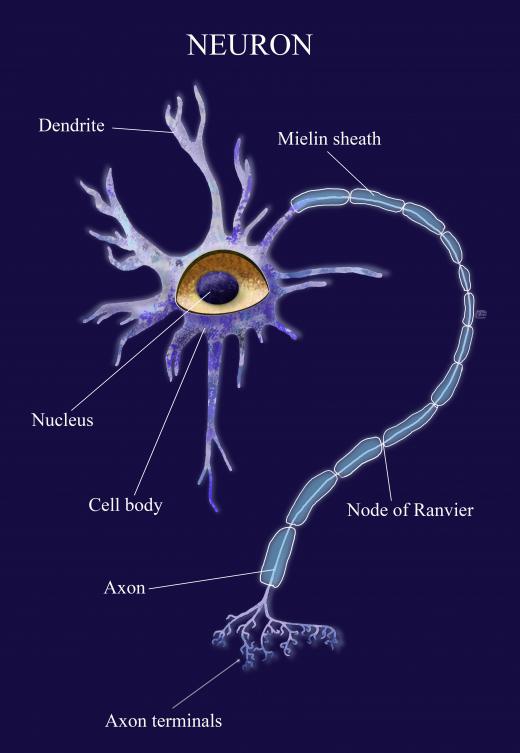

The motor cortex works in harmony with the premotor areas in the frontal cortex to plan out and execute voluntary movement. It is made up of Betz cells, special neurons that send axons down into the spinal cord. These axons communicate with spinal neurons by synaptic transmission. Betz cells are the largest neurons in the central nervous system and project into all the layers of the cortex.

Damage or lesions to the motor cortex can lead to paralysis or difficulty with voluntary motor control. The paralysis will be on the contralateral part of the body, so if the right side of the cortex is damaged, the left side of the body will be affected. Damage to this area can also interfere with the learning of motor skills.

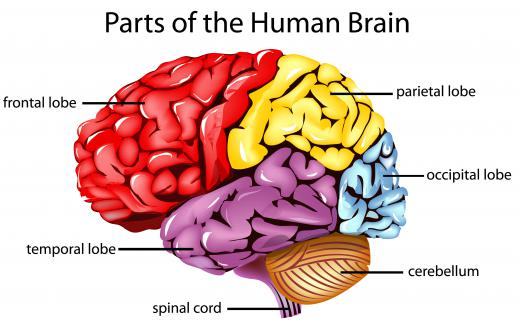

The central sulcus is a wrinkle in the brain that divides the frontal and parietal lobes. It runs down the middle of the brain. The motor cortex is just on the anterior side of this divide. On the other side is the somatosensory cortex, which manages sensory information from the body.

Neurons in the motor cortex send signals down axons located in the white matter of the cerebrum. These signals continue to travel down to the brainstem, where they cross paths in the medulla oblongata and head to the contralateral side of the body. These neural signals continue down the lateral corticospinal tract where they connect to the lower motor neurons via interneurons or direct synaptic connections.

The motor cortex can be mapped out as providing motor control to different parts of the body. The “homunculus” is a distorted representation of the body spread across the cortex. The hand and arm are enlarged, indicating finer voluntary motor control in these regions. In people who do specialized motor movements frequently, such as pianists, the finger regions may be even larger. If the body undergoes major changes such as amputation, the representational map of the body on the cortex will change also.

AS FEATURED ON:

AS FEATURED ON:

Discussion Comments

@David09 - Yeah, you don’t really appreciate what the primary motor cortex can do unless you lose its ability.

I consider the whole brain to be a computer, sending out thousands of processing instructions on a daily basis. It also raises the more philosophical question too, of whether you are still considered “alive” if there is electrical activity in the brain, although your body is otherwise deemed to be dead.

People have been kept alive in comas for some time, and in rare, somewhat miraculous instances, have suddenly emerged from their condition, with their brain and other organs functioning once again.

Whenever I see someone as brilliant as Stephen Hawking suffering from motor neuron disease, it makes me feel sad that such a great intellect has been paralyzed by a debilitating condition.

I am glad that computer interface technology has at least enabled Hawking to somewhat compensate for his disease, so that he can communicate and continue to write books.

At the same time, I also gain new appreciation for the motor cortex function, and the activities that the brain coordinates without our really thinking about them.

I believe that the brain is an amazing organ indeed, both in its ability to send signals to conduct both voluntary and involuntary movements.

Post your comments