What Is the Supercontinent Cycle?

Michael Anissimov

Michael Anissimov

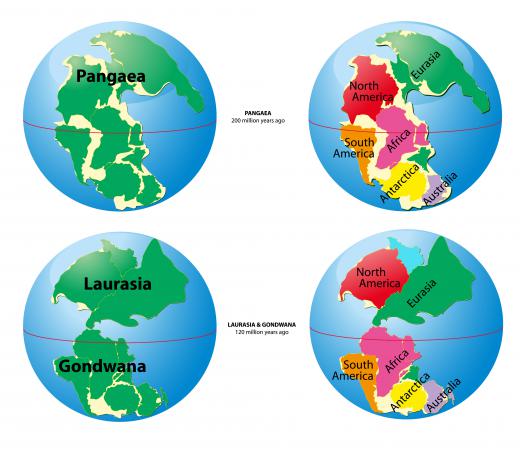

The supercontinent cycle is a geologic cycle where the Earth's continents alternatively merge into a single supercontinent, split into numerous continents, then merge again. The cycle is estimated to be 300 - 500 million years long. The supercontinent cycle is simply the result of geometry; given that about 29% of the Earth's surface is composed of continents resting on tectonic plates moving in a roughly random fashion, after a certain length of time, these continents will eventually aggregate and stick. But they won't stick forever -- rifting events between the continental plates cause them to move apart again, and the supercontinent cycle continues.

Previous supercontinents have included Pangaea, which formed 250 million years ago, Gondwanaland, which formed about 600 million years ago, Rodinia, which existed ~1.1 billion to ~750 million years ago, Columbia, which existed ~1.8 to 1.5 billion years ago., Kenorland, which existed ~2.7 to ~2.1 billion years ago, Ur, which existed ~3 billion years ago, and Vaalbara, which existed ~3.6 to ~2.8 billion years ago. Before this, the Earth did not have very much continental crust and thus no supercontinent cycle.

The Earth's climate may be remarkably different depending on where the Earth's landmasses are in the supercontinent cycle, and where they are located on the Earth's surface. For instance, when a continent has stalled around a pole, as is the case with Antarctica, it may grow a continent-wide ice sheet which significantly lowers temperatures around the pole. The cold water absorbs heat from the equatorial currents, lowering temperature worldwide.

In general, coasts of the world tend to be wetter places and thus more conducive to life. When the world's landmasses are at the supercontinent phase of the supercontinent cycle, the world's coastlines are decreased, and the center of the supercontinent turns into a vast desert. About 250 million years ago, at the dawn of the Mesozoic, the center of the continent Pangaea was a vast desert, wandered by the few tetrapod vertebrates which survived the Permian-Triassic extinction before it.

AS FEATURED ON:

AS FEATURED ON:

Discussion Comments

@Melonlity -- Proof? Well, there's not enough to elevate this notion from a theory to a fact. But that's the fun of science, isn't it? Digging up enough facts to support a theory is part of the challenge.

Fascinating theory that every student runs across at some point in a geology class. The theory is given more credibility when you look at the individual continents and see how they could fit together (roughly, at least).

Again, it is an interesting theory, but how much proof is out there to support it?

Post your comments